Subtitle: Discover how virtual reality can potentially transform physiotherapy processes for stroke survivors with visuospatial neglect.

Keywords: Virtual Reality, Visuospatial Neglect, Stroke Rehabilitation

Introduction: Did you know that after a stroke, nearly one-third of survivors face a challenging condition known as ‘neglect’? This neurological disorder significantly impacts their rehabilitation, affecting motor skills and critical aspects like spatial awareness. Visuospatial Neglect (VSN) is particularly notable, where patients struggle to notice things in part of their visual field, often on the left side. This not only increases fall risks but also adds to caregiver stress. Traditional rehab can be tough on both patients and therapists, leading to motivation issues. That’s where cutting-edge solutions like Serious Games and Virtual Reality (VR) come in! They’re blending with standard rehab methods, promising more engaging and effective treatment experiences. But there’s still much to learn, especially about how visual-audio cues in VR can help those with VSN, which is exactly what our study aims to uncover.

Main body: In our project, we’ve crafted a unique VR task for stroke survivors dealing with neglect. It’s all about using cutting-edge tech like Unity3D, VR headsets, and motion controllers to make physiotherapy more effective and engaging. We focused on how sight and sound cues can help patients during therapy. The task was fine-tuned with physiotherapists to be just right – not too easy, not too hard, and perfectly in sync with physiotherapy standards. It’s a game-changer in rehabilitation, combining tech with tailored care!

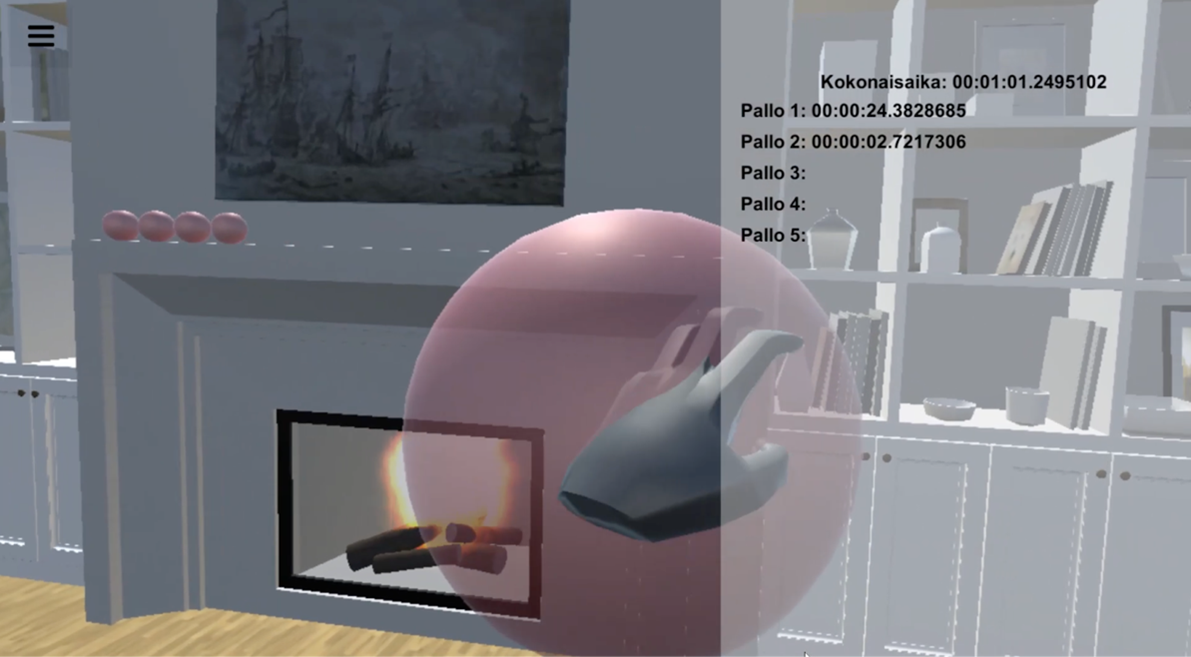

- Revamping physiotherapy with VR and serious gaming, this study takes a leap into immersive rehabilitation. This approach isn’t just about technology; it’s tailored for each person, enhancing motivation and addressing specific needs. The focus? A unique VR-based hand grasping exercise, decked with visual-audio cues, a fresh concept in Visuospatial Neglect (VSN) rehab. We’re exploring uncharted territory – how this VR task influences patient performance through physiotherapy sessions. It’s a blend of cutting-edge tech and personalized care, aiming to transform how we approach rehabilitation in VSN patients. Our VR task, a modern twist on a classic rehab technique, is a high-tech game for stroke recovery. It’s based on an exercise where patients reach toward a ball object in VR just out of sight. In VR, this gets supercharged. Patients reach for virtual objects in their ignored visual space, a smart way to mix perception and movement therapy. They’re not just reaching; they’re relearning how to move and see the world. And with audio cues added, it’s like a nudge, guiding them where to look and reach next.

- It’s all about making therapy engaging safe, and tailored, turning hard work into something a bit more fun and a lot more effective. Imagine playing a game where you’re in a cozy virtual room with a fireplace and windows, and your mission is to catch a bouncing ball that appears to your left. Each time you catch it, the game resets with a new ball. The twist? You’re actually participating in a cutting-edge VR physiotherapy session, designed to improve your spatial awareness and reaction time after a stroke. This isn’t just any game; it’s a clever blend of therapy and technology, where catching virtual ball objects helps rebuild real-life skills.

- This close guidance boosted patient confidence and adherence to the therapy. Interestingly, our findings, though preliminary, showed varied responses. One patient’s task completion time improved with added audio cues, while the other didn’t show the same pattern.

- This difference underscores how personalized VR therapy can be – what works for one might not for another. It’s a fascinating glimpse into the future of tailored rehabilitation, reminding us that every stroke survivor’s journey is unique. To read the full study visit: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2312.12399.pdf

Authors and Affiliations:

Andrew Danso1,2, Patti Nijhuis1,2, Alessandro Ansani1,2, Martin Hartmann1,2, Gulnara Minkkinen1,2, Geoff Luck1,2, Joshua S. Bamford 1,2,3, Sarah Faber 4,5, Kat Agres 6, Solange Glasser 7, Teppo Särkämö1,8, Rebekah Rousi 9, Marc R. Thompson1,2

1 Centre of Excellence in Music, Mind, Body and Brain, Universities of Jyväskylä and Helsinki, Finland

2 Department of Music, Arts and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä, Finland

3 Institute of Human Sciences, University of Oxford, UK

4 University of Toronto

5 Institute for Neuroscience and Neurotechnology, Simon Fraser University

6 Centre for Music and Health, Yong Siew Toh Conservatory of Music, National University of Singapore, Singapore

7 The Melbourne Conservatorium of Music, The University of Melbourne, Australia

8 Cognitive Brain Research Unit, Department of Psychology and Logopedics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

9 School of Marketing and Communication, Communication Studies, University of Vaasa, Finland

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.